Three Good Questions (and some answers)

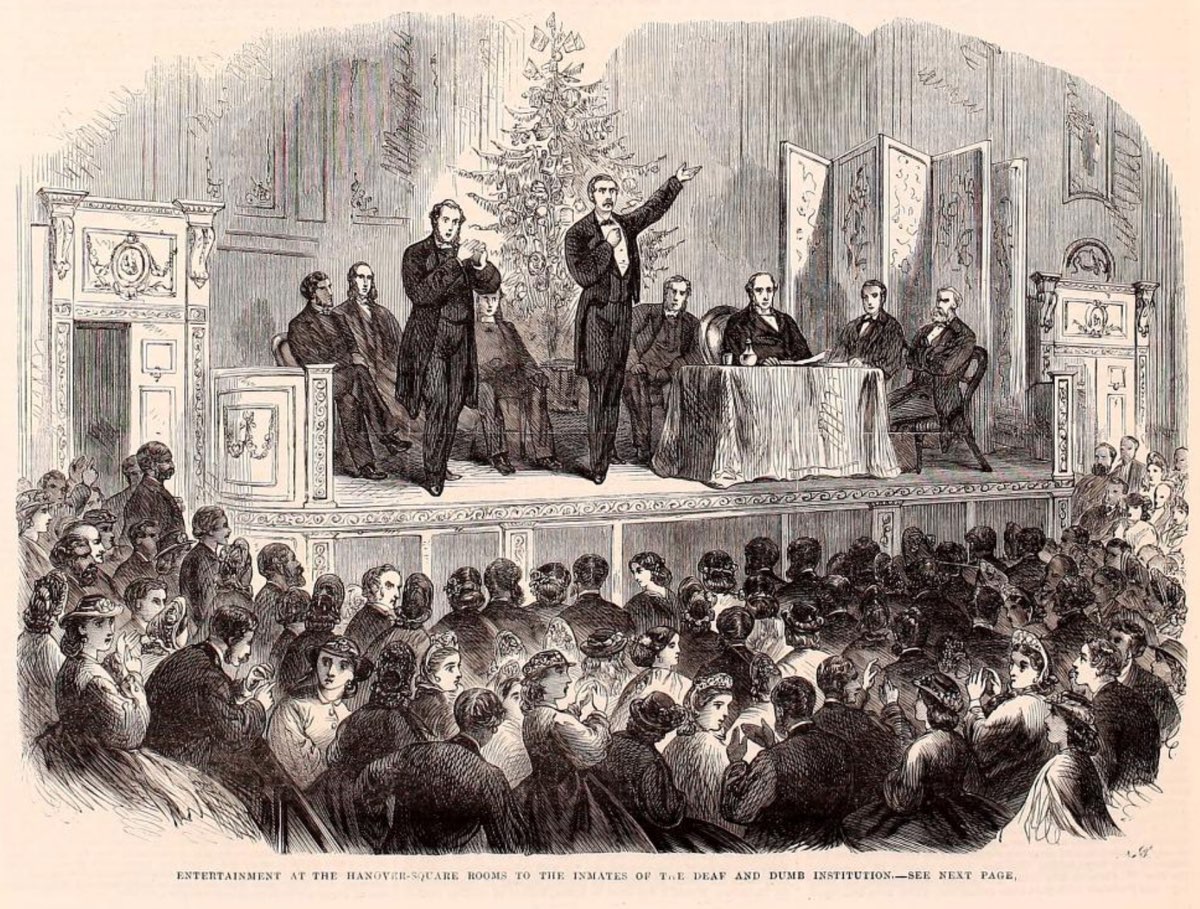

Last month I invited you to imagine that while doing some historical research you’d found an article about a fundraising event for the Deaf community published in the Illustrated London News on 21st January 1865. What could you learn from it? How many research rabbit holes would it lead you down? In what new directions might it take your writing? And, if you interrogated the image and words closely, what Three Good Questions would you want answers to first?

You can refer back to the full transcript of the article here.

My own Three Good Questions to get things started were:

- Why were the people without hearing referred to as deaf “and dumb” at that time?

- If the fundraising soirée was only the second event of its kind in two years, was the association still relatively new? (and did it go on to flourish for the benefit of the Deaf community?)

- Was the “finger language” in use in 1865 the same as modern British Sign Language?

To which my newsletter subscribers and social media followers added the following:

- What provision was there at the time for the education of Deaf children, particularly pauper children?

- Was Lord Carbery able to use his position to further contribute to the cause (financially, or through his influence)?

- Were any Deaf people included in the list of “subscribers and friends of the association” (indeed, any of the drivers of the association?), or were they all relegated to the position of beneficiaries?

In 1841, the Refuge for the Deaf and Dumb was founded by George Crouch, a bookseller with five deaf children, to train Deaf young men for trades, and educate those with no previous schooling. (1)

By 1854 the organisation had evolved into the Association in Aid of the Deaf and Dumb with an overtly evangelical Christian outlook. It had a team of missionaries who visited members of the Deaf community in their own homes to help them into work and to deliver Anglican services in sign language. It became the Royal Association in Aid of Deaf People in 1986 (without the evangelism) and is now the Royal Association for Deaf people.

By the time of the 1865 fundraising soirée, the association was therefore in its eleventh year (of that incarnation.)

(Quite separately, the British Deaf and Dumb Association was founded in Leeds on 24th July 1890. It aimed to, “elevate the education and social status of the Deaf and Dumb in the United Kingdom.” In 1971, “and Dumb” was removed from the association’s name.)

The first annual meeting of the Association in Aid of the Deaf and Dumb took place at 15 Bedford Row in London on 30th April 1855. In the press-reported minutes of the meeting, the chairman, Whig MP Lord Robert Grosvenor, reminded the committee of how the association, “arose out of an institution established some time since in the Old Kent-road, for the reception of deaf and dumb persons born of poor parents.”

The Reverend E. Auriol of St. Dunstan’s commented that the, “deaf and dumb constituted a class peculiarly appealing to Christian sympathy. They were, by their natural misfortunes, excluded from ordinary agencies…”

The Reverend John Davies of St. Clement’s in Worcester referred to the, “intellectual capacity and moral and religious sensibility possessed by deaf mutes.” He went on to point out that across the country there were, “12,500 deaf and dumb persons, not one-tenth of whom had been brought under religious instruction,” and that an, “uninstructed deaf mute was a most melancholy spectacle. In some places, and at certain periods, such persons were looked upon almost as idiotic, without any intellectual powers, and as such were kept in an asylum specially set apart for them.”

The asylum mentioned is almost certainly the London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, the first free school for Deaf children of the poor in Britain. It was founded in 1792 by the Reverend John Townsend on Grange Road in Bermondsey and moved to the Old Kent Road in Southwark in 1809. It remained in operation until 1902 when it was replaced by the Old Kent Road School. (2) A private Academy for the Deaf had opened in Edinburgh in 1760. (5)

Following the opening of the London asylum [“asylum” here being used in the sense of “refuge” rather than implying the place was an institution related to mental health, despite the implication made by the Reverend John Davies], a network of educated deaf people spread across the city. By 1840, philanthropically-minded people [such as George Crouch], deaf and hearing, had realised that communicating with signs and written English was no guarantee of gaining successful employment in hearing society. (3)

Returning to the meeting minutes from 1855, the Reverend J.B. Owen of St. John’s Chapel on Bedford Row, said that he, “had known many deaf mutes,” and that he believed their, “defect was, so to speak, a mechanical one; and if by mechanical contrivances that defect could be remedied, the same general effects might be produced on their minds by education, as were produced in the minds of others. Some deaf mutes, indeed, seemed to have even greater capacity than others, owing doubtless to that wonderful principle of compensation which the Creator had established.”

The words “dumb” and “mute” are used interchangeably throughout the minutes, always in the context of an absence of the use of speech rather than to a lack of intellectual capacity.

In 19th-century British English “mute” and “dumb” both meant “non-speaking”, and were not (intentionally) pejorative terms. They were used to identify people who were either deaf and used sign language, or were both deaf and could not speak (or had some degree of speaking ability, but choose not to speak because of the negative or unwanted attention attracted by atypical voices.) The North American pejorative usage of the word “dumb” to imply stupidity was first noted in the UK in 1928. (4)

Hearing people’s awareness that Deaf people not speaking was in some way related to their deafness, and was not a reflection of their intelligence, is reiterated in Reflections On The Natural Condition Of The Deaf And Dumb by James Foulston, Principal of the (Irish) National Institution for Deaf and Dumb, published by G. Herbert, Dublin, also in 1855. The book is described in the press of the time as referring to, “…the true relation between the want of the faculty of hearing and that of speech, the latter being dependent on the former…” However, it also underscores a prevailing attitude held by many of the hearing-endowed evangelisers of the time when it says that, “…the moral disadvantages under which the deaf and dumb labour, and their consequent proneness to yield to the baser passions of our nature, in a greater degree than is the case with those who enjoy all the faculties through which [religious] instruction can be conveyed.”

The report of the 1855 annual meeting of the Association in Aid of the Deaf and Dumb includes an account of monies received from 54 subscribers and donors. The list doesn’t indicate each person’s hearing status. However, “Lady Carberry, Freke Castle, Co. York” (a pair of typesetting errors, it should read: Lady Carbery, Freke Castle, Co. Cork) is shown as having donated a sum of £5.

Lord Carbery isn’t mentioned anywhere in the report. It would be interesting to know if Lady Carbery made the donation on behalf of her husband (and, if so, why?) or if she was acting independently from him, perhaps with the intention of encouraging his patronage.

While a proportion of the 19th-century Deaf community were inevitably born without hearing, many were made deaf during childhood by diseases such as Scarlet Fever. (2) I’ve not found a source to confirm which category Lord Carbery fell into. However, neither have I found any mention of family members also being deaf, which perhaps suggests his condition was the result of disease rather than genetic inheritance.

Lord Carbery, whose full name was George Patrick Percy Evans-Freke, was born on 17th March 1807. On 12th May 1845 he succeeded as the 7th Baron Carbery and the 3rd Baronet Evans-Freke of Castle Freke in County Cork, Ireland. He married Harriet Maria Catherine Shuldham on 5th August 1852 in Cork. They had one daughter, Georgina, on 3rd November 1853.

In a Deed of Settlement signed by both Lord and Lady Carbery three months after their marriage, Lord Carbery is recorded as being, “Deaf and Dum [sic], but being capable of reading.” The Peerage notes that he, “conversed on a slate.”

At the time of the 1865 fundraising soirée, Lord Carbery was approaching his 58th birthday. I’ve not yet found any evidence of how else he may have supported the Deaf community. He died on 25th November 1889 at the age of 82, five years after the death of his wife.

The other question I wanted to research was whether the “finger language” in use in 1865 was the same as modern British Sign Language? In the sense likely intended by the journalist, the short answer seems to be yes. However, the use of signs and finger spelling are separate skills, which together form what is now referred to as British Sign Language.

In 1698, an anonymous Deaf author published Digiti Lingua, containing manual alphabet charts that laid the foundation for the British Sign Language two-handed alphabet. (5)

The Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf was held in Milan in 1880 and attended mainly by hearing teachers of deaf children. It passed a resolution banning the use of sign languages throughout the world. Enthused delegates returned home from all over Europe to weed out Deaf teachers, to eradicate the use of sign language in schools, and to cut down classes to sizes that could be managed by hearing teachers. The British Deaf and Dumb Association was subsequently founded at a time of intense controversy about the use of sign language and finger-spelling in the education of deaf children, and about the exclusion of Deaf people from national decisions that affected their lives. In a world dominated by hearing people, hearing people acted on behalf of Deaf people, but they did not represent their true interests or share their aspirations. (6)

The Elementary Education (Deaf and Blind Children) Act was passed in 1893, which accepted, in full, the recommendations of the Milan Congress and led to an era of Oralism in British Deaf schools. British Sign Language wasn’t officially recognised by the British Government until 2003. (5)

Figures quoted by The Elizabeth Foundation suggest that around 1,460 babies are born deaf each year in the UK, with many more being born with some degree of hearing impairment, while according to the Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID), one in five adults in the UK today are deaf, have hearing loss or tinnitus.

If you know or discover any more about any of the people and organisations mentioned in this post, or if you’d like to suggest further questions, please do tell me via the comments below.

Sources:

1. Linda Isaac (ed), Full Circle: The History of RAD, Royal Association for Deaf people

2. H Dominic W Stiles, London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, UCL Ear Institute & Action on Hearing Loss Libraries, 2012

3. John Lyons, On becoming (Paid) Deaf Missionaries in 1870s London: The Life and Times of Samuel W. North and John P. Gloyn, paper presented at Social History Society Conference, Lincoln, 2019

4. Wikipedia (with references), Deaf-mute