Three Good Questions (and some answers)

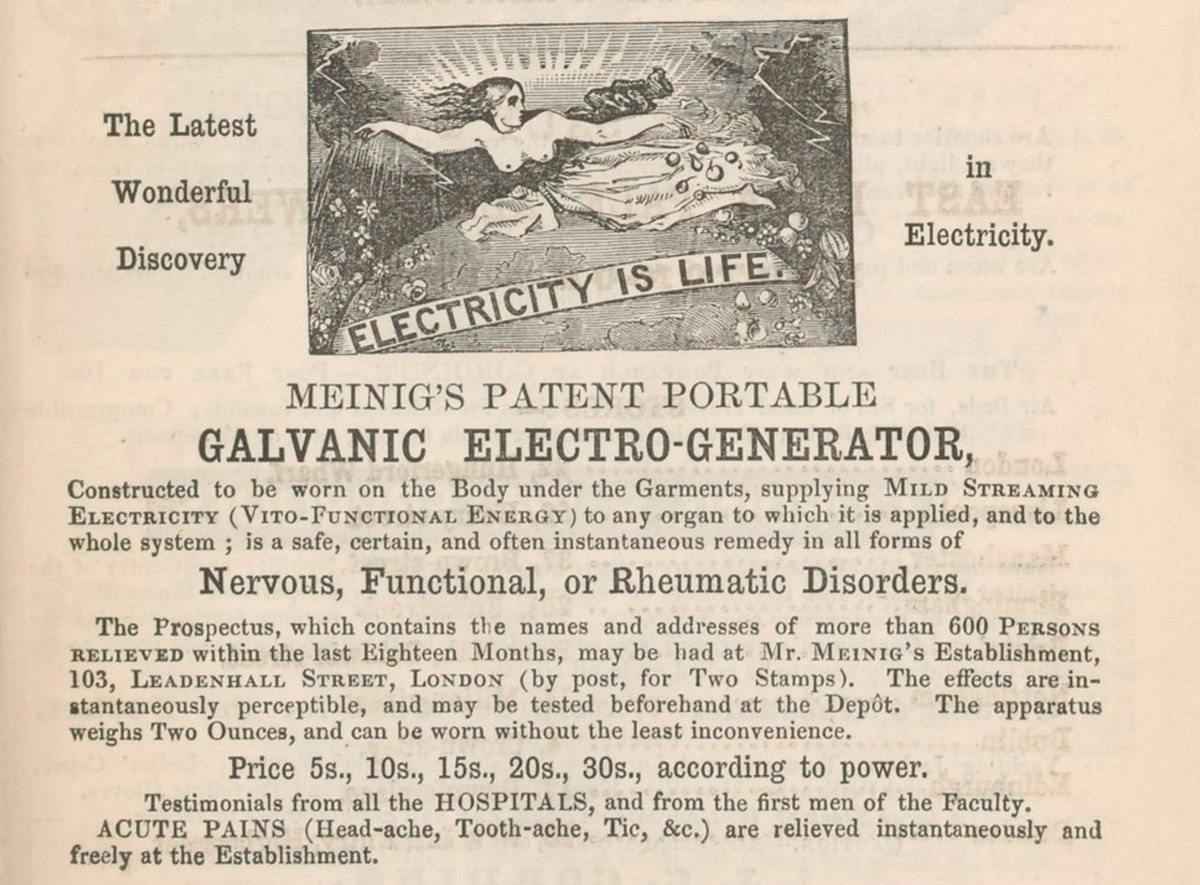

Last month I invited you to imagine that while doing some historical research you’d noticed an advert for Meinig’s Patent Portable Galvanic Electro-Generator in the 1854 edition of Hart’s Annual Army List. What could you learn from it? How many research rabbit holes would it lead you down? In what new directions might it take your writing? And, if you interrogated the advert closely, what Three Good Questions would you want answers to first?

My own Three Good Questions to get things started were:

- Who was Mr. Meinig? (and was he in any way medically qualified?)

- What did a two-ounce Galvanic Electro-Generator look like?

- Was this blatant quackery or did it actually have some therapeutic benefits?

To which my newsletter subscribers and social media followers added variations of the following:

- If the device was worn under clothing, how was it powered up (if the user was in the theatre, for instance)?

- What was meant by “mild streaming electricity”?

- What would you get for the top price of 30s.?

- What were the other discoveries?

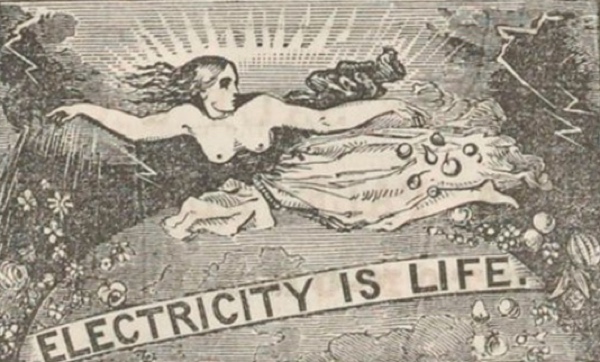

- Why was it being advertised with the image of a half-naked woman?

The science and practical applications of electricity were the subjects of intense research during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, from Benjamin Franklin’s experiments into the nature of lightning in the summer of 1752 and Luigi Galvani’s discovery of bioelectromagnetics in 1791, to Alessandro Volta’s 1800 development of the first battery (voltaic pile) and Michael Faraday’s invention of the electric motor in 1821.

One of the 19th century’s pioneers of the use of electricity in the field of medicine was a British doctor called Golding Bird, a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and a member of the London Electrical Society. (1) In the June 1846 issue of The Lancet, for instance, he contributed an article entitled: On The Employment Of Electro-Magnetic Currents In The Treatment Of Paralysis.

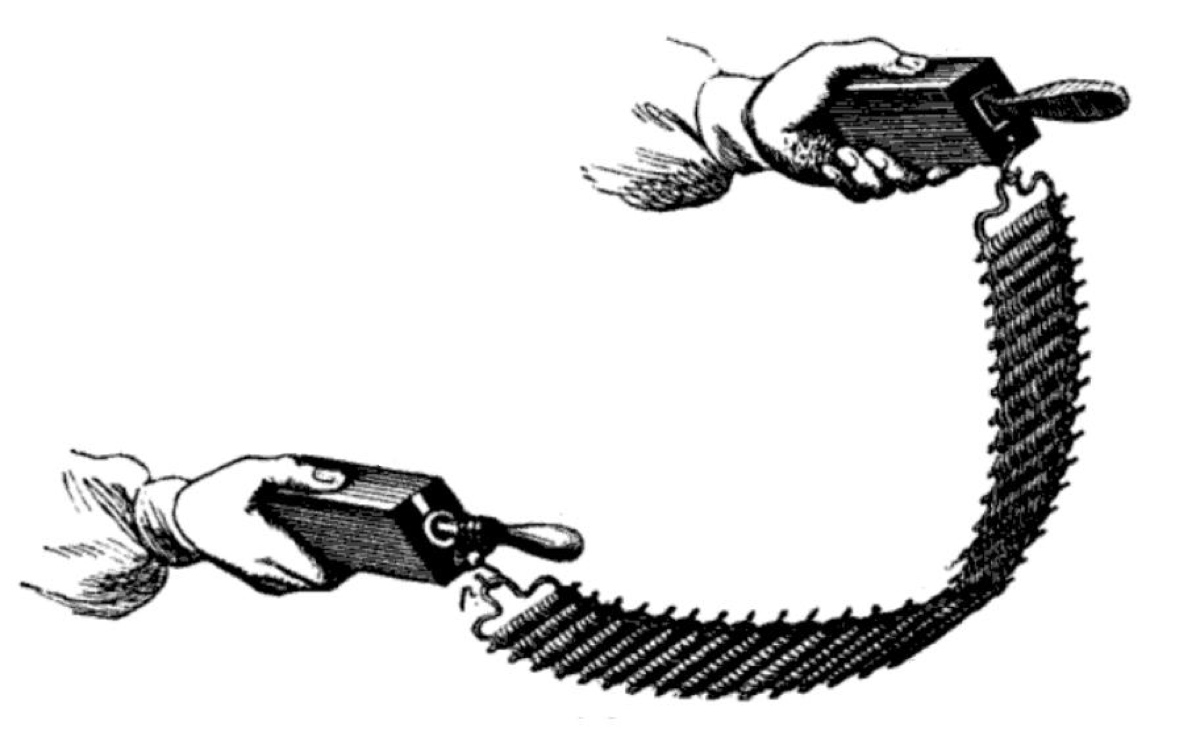

In 1851 Dr. Bird received a visit from a Prussian-born electrical engineer by the name of Isaac Louis Pulvermacher. Speaking very poor English, he presented a sample of his invention of a galvanic chain, or “Magic Band”, for evaluation. An adaptation of the voltaic pile, each cell in the chain consisted of a wooden rod concentrically wound with copper and zinc wires. These sat in grooves that brought the wires close to each other without touching. Soaking the rods in an electrolyte, such as vinegar, activated the battery action and by connecting many rods in series the voltage could be increased to high levels. Dr. Bird found the basic device useful for experimentation and was persuaded to write a testimonial with the objective of introducing the device to doctors in Edinburgh. (2)

It is at this point that Charles Ludovic Augustus Meinig enters the story as what we would now think of as Isaac Pulvermacher’s sales and marketing agent. In a series of newspaper advertisements, including the medical press, he made the most preposterous claims backed up by Dr. Bird’s testimonial (although it doesn’t feature in the Hart’s New Annual Army List advert.) Charles Meinig sometimes gave himself the title of “Doctor”, but was not medically qualified. Dr. Bird complained about the misrepresentation of his comments, but the energetic Meinig ignored threats of legal action and set about establishing an extensive network of stockists and agents. (2)

What differentiated the product variations in terms of price seems to be the number of rods in each chain. The more a customer paid, the longer the chain.

1856 illustration of Pulvermacher’s Galvanic Chain (the function of the boxed handles is unclear)

In a letter to the editor of the Association Medical Journal on 4th April 1853, Dr. Golding Bird wrote:

The chains usually sold are too feeble to afford a sensible shock or even any physiological sensation; they are, moreover, often directed to be worn round the body, in which case, as every link would come in contact with the skin, no concentration of force, no current, would be developed at the poles…

…I can only deeply regret that a certificate given in faith to recommend a scientific instrument to the notice our profession, should have been employed to advocate it a quack remedy [my emphasis]. As I stated in the Lancet in 1851, “It must be recollected that the current evolved has no peculiar properties and that it will effect nothing more than that evolved by any other means. It is indeed deeply to be regretted that so convenient a source of electricity runs the risk of losing favour in the sight of educated men generally, and of our profession in particular, by being injudiciously puffed in the public prints by advertisements claiming for it a medical influence it in no wise possesses.”

In response, the Association Medical Journal stopped printing Meinig’s adverts in 1853. However, despite Dr. Golding Bird’s death in October 1854, mention of his disputed testimonial still featured in Meinig’s advertising in The Lancet throughout 1855.

How much of Meinig’s Electro-Generator was based on Pulvermacher’s device is not known. He may even have been selling existing stocks of the Pulvermacher chain under his own name. Meinig continued to advertise until at least 1859, at which point there seems to be no further coverage in the newspapers. However, Isaac Pulvermacher continued in the same promotional vein, also quoting Dr. Bird’s testimonial, and the company he founded remained in business until 1951. (2)

As for why Meinig’s 1854 advert in Hart’s New Annual Army List features a half-naked woman above the “Electricity Is Life” slogan, a fair degree of speculation is required.

Emerging from a tree (or is it a thunder cloud?) riven by lightning, and bestowing a life-giving bounty of fruit and flowers, on close inspection the female figure appears to be a variety of nymph, a nature deity from ancient Greek folklore. In art and literature, nymphs have always tended to be depicted naked or semi-naked. (4) In that respect at least the advert might be said to be in keeping with convention.

Statue of a sleeping water nymph in the Grotto at Stourhead, Wiltshire

Unlike the general press, the target audience for Hart’s New Annual Army List was primarily British Army officers and civil servants (i.e. men from privileged backgrounds who’d received classical educations) with whom the nymph symbolism might be expected to resonate. On the other hand, Meinig may simply have chosen an image he thought might titillate a male readership. Given his overall approach to marketing, that much less cultured explanation is perhaps the more likely one.

Meinig and Pulvermacher’s marketing methods may not have been ethical, but they certainly achieved their aim of generating widespread product awareness. Pulvermacher’s hydro-electric chains, for example, made a cameo appearance in Gustave Flaubert’s 1856 novel, Madame Bovary. (3) A week before his death in June 1870, Charles Dickens ordered a voltaic chain from Pulvermacher & Co. in the hope it might relieve his gout. (2) In 1907, unnamed “… sellers of invigorating electric belts…” are mentioned in Joseph Conrad’s novel, The Secret Agent, as being like the story’s protagonist and, “…men who live on the vices, the follies, or the baser fears of mankind…”

Electrotherapy continues to play a role in modern medical and sports rehabilitation practices, although its effectiveness in different contexts is widely debated. (5)

If you know or discover any more about any of the people and devices mentioned in this post, or if you’d like to suggest further questions, please do tell me via the comments below.

Sources:

1. Wikipedia (with references), Golding Bird.

2. Alan Gall, Pulvermacher’s patent portable hydro-electric voltaic chain, The Journal, The Institute of Science and Technology, Winter, 2012, Pages 40-47, ISSN 2040-1868.

3. Robert K. Waits, Chapter 11 – Gustave Flaubert, Charles Dickens, and Isaac Pulvermacher’s “Magic Band”, Progress in Brain Research, Elsevier, Volume 205, 2013, Pages 219-239, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63273-9.00018-6.

4. Wikipedia (with references), Nymph.

5. Wikipedia (with references), Electrotherapy.