I didn’t stay long enough at Meikle Ferry to ever sail with the target boats, for my detachment was cancelled and I was ordered back to Evanton at once. I was delighted, but my joy was short lived for the reason for my return was to be given leave prior to being posted abroad. This was the one thing I had always dreaded as I knew that, except for Iraq, most overseas postings were for a period of five years, though it was more the thought of the troop ships than the actual service that bothered me.

Anyway there was no way out so I had to have the usual injections, vaccinations, etc., and to resign myself to the inevitable. One stroke of good fortune turned up at the last moment. There were no troopships available at that moment and I was therefore to travel tourist class with twenty-six other chaps, in civilian clothes, aboard the SS Strathnaver sailing from Tilbury via the Mediterranean to India.

I don’t recall how I got to Tilbury. Suffice it to say that I joined up with my fellow travellers and went on board in civvies as instructed. We were four to a cabin, which was just above the water line, and for the next three weeks we were to live like lords.

We sailed on Friday, 13th May 1938. Engines throbbing steadily beneath us, we headed out into the English Channel. Overhead the sky had darkened and a fresh breeze whipped the water into white caps.

We were fearful of what to expect when we passed through the Bay of Biscay. I had always imagined that the Bay of Biscay would be terribly rough, but in fact it was as smooth as a millpond and before we knew it we were putting in at Gibraltar. Here we went ashore and enjoyed all the usual sights which visitors are shown, and of course the local shopkeepers made hay whilst the sun shone. I don’t know how many passengers were travelling on the Strathnaver, but certainly most of them would spend quite a bit on souvenirs.

Our next port of call was Marseilles. Three of us went ashore and explored the city on foot, eventually ending up at the cathedral. A young Frenchman who could speak English offered to show us round and it was not until we came out that we realised he had an ulterior motive, viz. the selling of dirty postcards and offering to get us fixed up with his “lovely girls” at 20 francs per time. He wouldn’t be put off and in the end we had a shouting match with him in one of the main streets until a gendarme came along and sent him packing.

We decided to take it in turns to try out our classroom French and it was my turn. I asked a rather stout chap in the sailors’ camp if he could tell us which tram to catch to take us back to La Place de la Garde. He spoke so quickly in reply that all we caught between us was soixante-six, the tram number. Fair enough, we waited until one came along and jumped on. It was a double tram and the conductor was in the rear compartment. By the time he got to us we had travelled quite a distance and when we stated our destination he threw up his hands in despair, stopped the tram and pointed violently back in the direction from which we had come, shouting “soixante-six” at the top of his voice. We had of course taken the right number tram, but should have gone in the opposite direction. Off we got and as there was a taxi parked by some iron gates near by we went over and tried again. The driver listened carefully to what we had to say and then shook us somewhat by saying in a broad cockney accent, “Okay mates, jump in.” We needed no second invitation and as he nipped along at terrific speed it was difficult to know whether our greatest fear was of being killed or the fact that his meter was ticking over so as to give the impression that it was vying with the car’s speed. Anyway we reached the ships berth, with a few centimes left amongst the three of us after paying off the taxi.

We all had to be on board by 6pm ready to up anchor once more. Amongst the passengers now there were several French families who had joined the ship at Marseilles, and also a number of young German students. These people were all bound for Australia and their presence was a source of interest to us. The French had the most peculiar table manners and at meal times would get their heads down and really get cracking on their food. It was possible to hear their jaws working even at the next table. The German students were just a wee bit arrogant and wore swastika badges in their button holes. In spite of this, however, they were very friendly and quite sincerely wished everyone good luck for the future when the time came for us to part company.

We made friends with an Indian doctor from Birmingham. He was going home to visit his parents and had left his English wife at home. He said he didn’t want to take her with him as the Indian customs and way of life wouldn’t suit her.

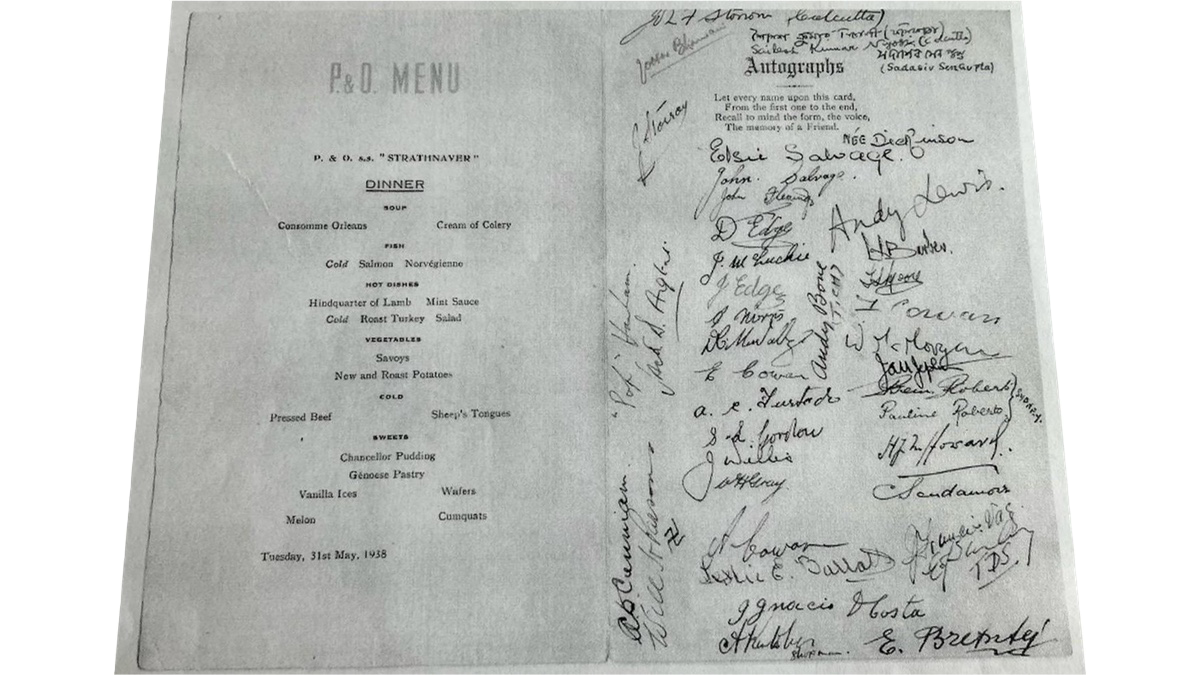

Passenger autographs on an SS Strathnaver dinner menu

During the daytime there were lots of deck games organised by the ship’s quartermaster and we were roped in to form a tug-of-war team. The semi-final was between our chaps and a team of hefty Palestinian policemen. Being much the frailer looking side the sympathies of the other passengers were all for us and they cheered and shouted encouragement as we heaved and strained against the foe. The incredible happened – on both pulls their anchor man slipped on the smooth deck and we were able to take advantage of their bad luck.

Just about this time we were passing through the Straits of Messina between Italy and Sicily. The volcano Stromboli was in eruption and clouds of steam rose from the sea as the molten lava flowed into the water. It was a fascinating spectacle and many of the passengers were busy taking cine films as we passed by. I myself took one “snapshot” but we were too far away and as it was dusk or near dusk it didn’t come out too well. One couldn’t expect too much from a 2a Brownie box camera I suppose!

We were all now looking forward to going ashore at Port Said and soon the customs house came into view. Numerous small craft scudded around the harbour, their sails gleaming in the bright sunshine. As the ship came to rest it was surrounded by dozens of small boats loaded with all kinds of trinkets, hand made baskets and goodness knows what else. The “bum-boat” men, as they were called, clambered up the side onto the main deck where they proceeded to sell their wares to the somewhat gullible passengers. There was even an exhibition of the Indian rope tricks and numerous other acts of magic such as chickens, which appeared from nowhere.

Ashore we all went then and of course after a quick look round the main part of town we headed for the photographic and jewellers shops where cameras, field glasses, watches and the like were going at bargain prices. Wherever we went we were besieged by would-be salesmen and it was extremely difficult to escape their attentions, so much so indeed that I, for one, was quite relieved when the time came for us to go back to the ship. The next stage in our journey took us down through the Suez Canal.

It was much narrower than I had imagined. The land on either side was quite flat with little interest except for an odd group of camels or a few dirty looking tents here and there. Although I didn’t know it at the time, we must have passed by the “Kantara” British cemetery 50 miles south of Port Said, where my father was buried in 1919. It was terribly hot down in our cabin and quite a number of passengers chose to sleep on the open deck. This was fine until lascars started hosing down at some unearthly hour in the morning. Having reached the entrance to the Red Sea we dropped anchor off Aden. We had been looking forward expectantly to seeing the R.A.F. station there, but owing to the troubled state of the protectorate at that time we were not allowed ashore. Onwards then, across the Indian Ocean, our time passing pleasantly enough, eating, drinking and sleeping and taking part in such deck games as the mood allowed, until wakening up one morning to find ourselves at anchor off Bombay. Great excitement as we hurriedly put on our khaki drill for the first time prior to going ashore.

What a sight! Our uniforms were all creased through being in our kit bags for three weeks and on top of that they were a dreadful fit. Anyway there was nothing we could do, so off we went by transport to the railway station. The place was alive with coolies, beggars and hundreds of other natives all pushing and shoving this way and that and jabbering away in their own language. It was here we heard our first whine of “Baksheesh sahib – no father, no mother, no sister, no brother – every day never coming sahib.” It was here too we came across betel nut, or at any rate the expectorated red stain all over the platform. Indeed spitting was one of the most revolting sights which befell our eyes and I think we all felt slightly nauseated.

It was all very strange and I think we were all getting just a trifle worried when our friend the Indian doctor, who had been our companion on the ship, came upon us and advised us to get ourselves a compartment straight away, and when we had settled in to come along the train to his compartment for a chat.

The compartment had four bunk beds in it, two of which were normal seats and two hanging from chains above. In the middle of the roof were two electric fans, which were mounted on swivels so that the air could be directed one way or another as desired. There was a w.c. and toilet with wash basin and mirror and all the windows had three shutters, one of glass, one of slatted wood and one of a fine wire mesh rather similar to the old fashioned metal cabinets used for keeping food and milk in before the days of fridges. So it was possible to shut out glare, dust and noise to quite a remarkable degree.

Having got ourselves comfortably sorted out we moved along the platform until we reached the doctor’s. He was waiting for us and had changed into his native Indian clothes. The change was quite startling and he suddenly seemed to have altered completely and was now just like many of the coolies who were jostling about on the platform. However, he made us welcome and proudly presented us to the three other occupants as his English friends. They seemed somewhat at a loss, which we couldn’t understand then, being new to the ways of the sahibs. One excellent idea we learned here and that was the advantage of having a metal bath tub containing a maund of ice immediately under the fans, and we procured a similar item of equipment on our return to our own compartment. As far as I recall the maund was somewhere in the region of 28 lbs in weight, but I cannot now be sure. He gave us one more useful tip and that was to the effect that there was in circulation a great number of forged coins, especially rupees. He showed us how to flick the coin into the air and how to judge its authenticity or otherwise by the sound it made as it left the thumb. A good sound coin gave off a clean tinkling sound whereas a “duff” one sounded dull and leaden.

Each morning at about 6am there would be a knock on our window and the guard would hand in a pot of tea and some toast and marmalade – this was chota hasri, or little breakfast. Real breakfast would be passed through the window at 8am and it was all nicely arranged in a wicker basket containing cups, saucers, knives, forks and spoons together with usually bacon and eggs, fried bread and tomatoes. I never ceased to marvel at how the guard managed to get it along the outside of the train whilst it was in motion.

From now on each day was just like the one before and we longed to be able to leave our cramped quarters and really stretch our legs more than just the length of the occasional railway platform. As we journeyed further and further north we noticed a change in the types of people thronging the platforms. They were now much fairer in colour with more aquiline features, and the type of dress had changed from the dhoti to a form of white baggy trousers. Another change, which was particularly noticeable, was the fact that there were armed police at nearly every station.

Introduction | Chapter 2 | Chapter 4