I was born at 8am on the 29th November 1916 at my father’s house: “Croftbank”, 22 Glebe Street, Hamilton. My father was away out east with the Royal Garrison Artillery, where he contracted typhus fever from which he died at the early age of 37 years. He was buried in “Kantara”, properly El Quantara, the British War Graves cemetery 50 miles south of Port Said in Egypt.

My mother died within a week of my birth and my father’s sister Christina from Carluke walked several miles, because of a train strike, to take me and my brother Alec to her home. My grandparents would not hear of it and with great courage, for they were not young, undertook to bring us up.

Naturally I remember very little of those early days but I have since learned that I was a seven month baby and needed constant and careful attention. A little later on I was out in my pram one day and I do remember seeing some overhanging foliage. I have never forgotten it and can still to this day pick out the exact spot outside Auchingrament parish church.

I used to sit on my grandfather’s knee in front of the kitchen fire and I have a very clear picture of when he was taken ill. He had a handle suspended from the ceiling above his bed with which to pull himself into a sitting position. His death brought a large number of relations to the funeral and I can still see their faces in my mind’s eye.

Prior to the war my father was employed in a small drapers shop in Chapel Street, Carluke, and used to walk five miles to and from his home at Townfoot Farm, Kilncadzow. Later on, right up to going off to the war, he was 1st Sales in Pauls London House, a drapers shop in Quarry Street who thought very highly of my father and who watched over my brother and I from a distance, and it was not unknown for him to slip us a halfcrown when we met him outside church on Sundays.

My mother’s sister, Aunt Net, had been married to Charles Fraser, but he had not long died and she had gone back to business as a secretary, at which I understand she was extremely efficient. Anyway she now came to live with us and I suppose I must have been about seven or eight years old when she remarried a really nice gentleman named Archibald Jack Alexander. I was present at the wedding, which took place in the parlour at our home in Glebe Street. The minister, a crippled old fellow, drove up in his pony and trap to perform the ceremony. In common with most Scottish weddings at this time the bridegroom scattered a handful of coins for the local children as the cab pulled away.

When I was about three years old they took me to see my first film at the Scala cinema at the Old Cross in Hamilton. It was a silent film of course, and I fell asleep leaning up against the man in the next seat, so I’m told, but I do remember the cartoon which was all about a cat which had got itself all tied up in string and ended up in a drawer – probably “Felix”!

When I was about five my granny took me along to St. John’s Grammar School primary section where I became a rather unwilling member of Miss Stodart’s class. She was a very stout lady and I was somewhat afraid of her. We boys had to join hands with a lot of girls and dance round in a big circle – I hated it!

Next door to us at number 20 lived the Smith family. Mr Smith was a milkman and had his own dairy complete with creamery, wash house and large stable which held four horses. At the far end he kept his lorry and this was always kept well painted and had his name along the side in gold letters. Above the stable was a loft, at one end of which he had pigeons and at the other end hay and straw. One had to climb up by means of hand and footholds to reach this paradise and many a happy hour I spent there with the younger Smith boys, Jimmy and Johnnie. There were three other sons, Tom the eldest, Adam the next and then Robbie, and then there were three daughters Jean, Janet and Margaret, and of course there was Darkie, the black spaniel dog.

Eventually Mr Smith decided to do away with his horses and in their place came a ”T” Ford lorry in gold leaf. The old Ford had no gear lever but was controlled by three pedals in the floor and a hand operated throttle on the column. When running the whole thing used to vibrate but it was nevertheless the pride and joy of the neighbourhood.

After some years this vehicle was replaced by a more modern Ford and also a bull-nosed Morris Cowley. This latter was a beautiful car, hand painted red with a black hood and the coach work was maintained in perfect condition always.

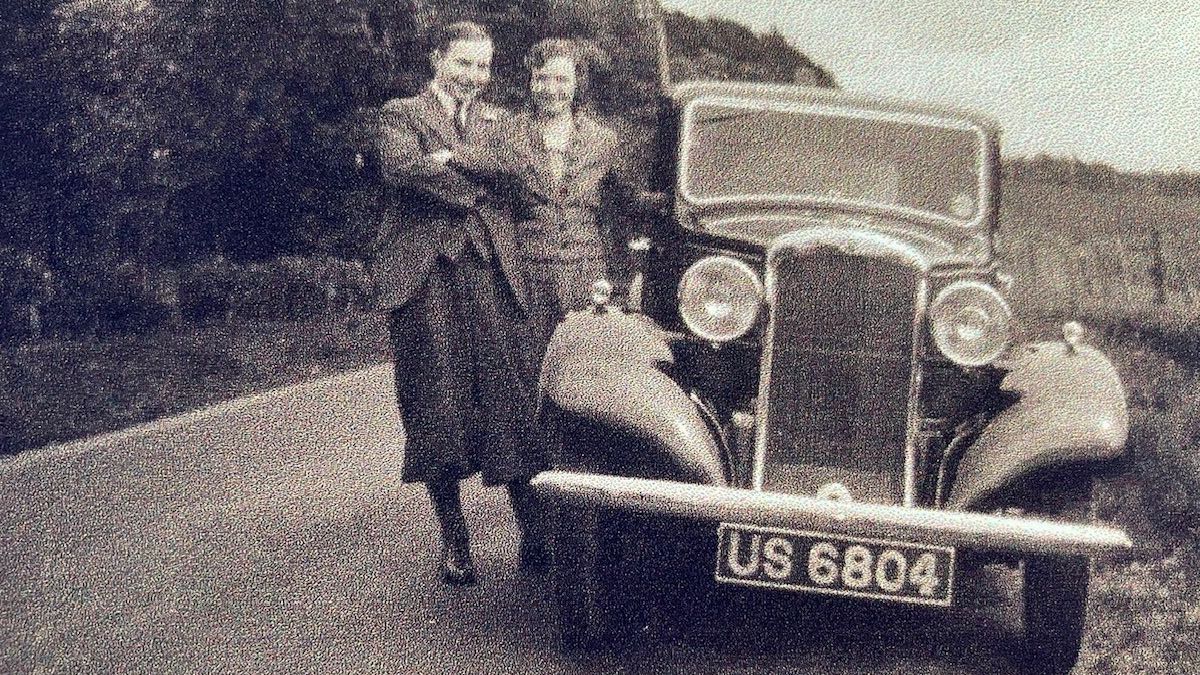

W.A. Hamilton with his cousin, Mary.

Alec used to play with the older Smith boys and, of course, cowboys and indians was just as big a favourite then as now. At the bottom end of their yard was a wooden paling and I remember how mad I was to see that they had tied Alec to it during one of their games. I didn’t appreciate that he was enjoying being tortured. When Robbie left school he went into the milk business with his father. He had an old Angus Sanderson two-seater car with a dickey at the back and this was used to carry the milk cans. He was a wild fellow at the wheel and was killed in a car crash in the end.

Aunt Net and Uncle Archie moved away now to live in their new home at number 16 Gala Street, Riddrie. In due course I went there for my holidays and I thought it was great. They had an upstairs and it was fun pretending that I was mountaineering. At night as I lay in bed I could hear the trams screeching as they rounded the corner near the shops.

Uncle Archie had a great love for his garden and he and Aunt Net spent many hours titivating it. She couldn’t bear to pass a garden, which had some plants which she didn’t have and thought nothing of leaning over and helping herself to a cutting.

Alec and I had been keen builders of crystal sets and I can remember how we tried to use our bed springs as an aerial and also the spokes of a bicycle wheel, but without success. We had two pairs of earphones wired up to our bed and we listened in to the BBC’s move from Savoy Hill to Broadcasting House. It was a great thrill as each new studio came on the air. I had never seen a valve set and so I was full of wonder when Uncle Archie at Riddrie bought one. It had two bright emitter valves on top and coils which could be brought together or moved further apart as required and a black Bakelite dial marked off in degrees. To crown it all, in addition to the usual headphones there was a large horn-shaped loud speaker which gave fairly good reproduction of voice and music when tuned properly so as to eliminate the whistles and other strange noises.

Aunt Net used to make what she called Bee’s wine and it was kept in a large glass bottle on the window sill and one could see the “bees” rising and falling. It tasted rather sweet and sickly.

My uncle was, in spite of his weight, a great walker and we used to roam for miles. Sometimes we would end up at Hoganfield Loch where we would hire a boat and row up and down the loch. I usually was in charge of the rudder. On the way home we’d call in at a little wooden shop and have a lemonade with ice cream. In the opposite direction to Hoganfield Loch was Cumbernauld Road and a little way along was the further attraction of a boating pond. Uncle and I used to sit and watch enthralled as the men, yes I mean men, took part in yacht races with models which must have ranged from 4ft – 6ft high at the mast.

Not long after this they moved home and went to live at Underwood Road, Burnside, near Rutherglen. Uncle would travel to Glasgow each day by train. He worked in Glasgow Corporation and was never without his umbrella and bowler hat when at work. When on holiday or at home he liked his flat cap and was always buying new ones.

Smoking was his only vice and he enjoyed his pipe immensely. Erinmore was his favourite tobacco but every time he smoked it in the house he used to get told off by my Aunt and so he would repair to his summerhouse where he could puff away to heart’s content.

The bungalow at Underwood Road was beautifully furnished with lush carpets and Regency style chairs etc. In one corner of the sitting room stood a china cabinet and there was also an HMV table gramophone and lots of records, some by Will Fyffe which I enjoyed and others like “In a Monastery Garden” and the odd rather high-falutin’ opera. There was a collection of Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas. Aunt Net was extremely house proud and one was not encouraged to use the sitting room overmuch or to disturb the cushions in any way.

My grandmother was seldom away from the house except to go shopping and she used to walk all the way to the town and back and I never once heard her complain. She did all her own washing and ironing and even turned her hand to decorating. I can see her now doing the ceiling with a distemper brush tied to the end of a broom handle. However when I was about ten years old Uncle Archie and Aunt Net took granny and me up to Perth to visit granny’s two sisters and their families. We travelled by an Alexanders coach and I remember being sick before we got there. Granny’s sister, Kate, lived with her daughter and son-in-law in a large rambling house just across the river from the railway station at the opposite end of the bridge.

There was one boy, Willie Hay, about my age and we used to play cricket on the North Inch. Halfway across the river was an island we used to go there fishing. The only thing I ever caught was a fluke, a small tiddler of a thing like a miniature plaice. Willie’s father had a good job at the salmon fisheries and he took us down there one day to see the huge fish spread out on the floor.

W.A. Hamilton playing cricket on North Inch

Granny had a brother, Peter Scott, who was a woodcutter and lived by himself in a little cottage by a stream in the village of Inver. Behind the house was a shed smelling strongly of pinewood in which he kept his saws, axes and other tools and these were a constant source of interest to me. The stream was crystal clear and teaming with minnows and other small fish but there was nothing of any size.

The cottage was furnished, not unexpectedly, with large heavy old furniture and there was one chest of drawers in which he kept a number of small but rather lovely gold watches. They were the pocket type but I believe they must have been ladies’, which would seem to indicate that he must have been a widower. Aunt Net was really taken with the name of the village and later named her bungalow at Burnside “Inver” after the village.

The nearest small town was Dunkeld situated some 15 miles from Perth and close by were Birnam Woods. There was a large house in the middle of these woods surrounded by a moat and reputed to be occupied by a hermit, but the Hermitage seemed always to be deserted and I certainly never saw him.

That holiday was all too soon over and we went back home. Granny and I to Hamilton, and Aunt Net and Uncle Archie to their own place.

One of my pals at this time was a fellow called Willie Gourlay who lived just down the road. At the back of his house was a shed well stocked with all kinds of chisels, hammers and the like which proved irresistible to us small boys. Many a happy hour we spent knocking up go-karts and so on from old pieces of timber and pram wheels. There was also a hen house but as it wasn’t used for hens, the door was kept padlocked. However when we wanted a really secret meeting place we would crawl in through the hole normally intended for the hens. It was a tight squeeze for me as I was somewhat on the fat side and I was really quite frightened in case I got stuck halfway.

Granny had a son, Peter, who was a solicitor in London and lived at Streatham. He made a practice of travelling north about once a year to visit her and of course that was always a great event not just because of the presents he might bring but he was quite a character and was a wonderful teller of tales. He always wore a blue pin-striped suit and spats. He was never without his cane and gloves and wore heavy horn rimmed glasses. All the kids thought he must be at least a Lord and would stand mouths agape when he passed by.

Granny always saw to it that there was a bottle of whisky in the house when he came and even got in a siphon of soda water from the little shop down in Bent Road. I think, however, that she felt he was trying to be the high and mighty one and this was especially evident when, on one visit, he announced that he had bought a house called Thurlow Towers and produced full plate photographs of the large hall, billiard room and balcony with its shields of spears, knobkerries, and just for good measure two suits of armour, reported to have come from the battle of Crecy. He was being far too grand, but really she laid the blame on his wife, Sally, who though a tiny little woman was a force to be reckoned with and got her way in most things.

Uncle Peter smoked Turkish cigarettes, which were not exactly the brand which found favour amongst the locals, and so this in itself used to draw peoples’ attention as he passed. He was a great man for walking and more often that not we would go down to the Whisky Well. This was just a stream really, which flowed along at the bottom of a fairly deep valley. Now it has all been built up and there is a council estate on top, the only remaining link being a pub called, not unnaturally, “The Whisky Well”.

My brother Alec being some seven years older than me went further afield at holiday times staying on my uncles’ farms for weeks at a time. However I did get as far as Carluke where my Aunt Christina, Uncle Archie and my cousin, Mary, lived. This was my favourite place of all. Uncle Archie was a cattle dealer and I loved going with him down to his fields each morning to feed his cattle and sheep. He had a bicycle fitted with a three-speed gear and it had a back step. I can see him now getting mounted. He never stood on the pedal, but always got up on the back step and threw himself forward onto the saddle.

Monday was market day at Lanark and we used to get there early and get a ringside seat to watch the cattle being sold. He seemed to know everyone and stop for a chat with this one and that as we moved back and forth between the various sale rings. As midday approached he would fish out his pocket-watch and say, “right Willie, let’s go and eat,” and off we’d set for a little restaurant just across from the market. The food was always well cooked and there was plenty of it, and I must confess I really did enjoy it. Afterwards it was back to the ring where perhaps he would buy some bullocks, lambs or pigs. These would be transported back to Carluke either to end up in his fields or in the slaughterhouse in Sandy Road. On our way home in the evening we would call in at the slaughterhouse and see his purchases hanging up on the steel hooks of the conveyor system. It was not unknown for him to cut out what he considered to be a particularly succulent piece of beef and kidney and hand them in at Eason the bakers in the High Street, to be made into a huge pie. My word, but they were really something those pies.

He rented a large area of moorland between Carluke and Lanark where he kept mainly sheep, but now and again he would have cattle there as well. Most of the time his activities were carried out in his fields on either side of the road just below Carluke railway station, and I always marveled at his familiar attitude to the railway staff and how he seemed free to roam across the line from one platform to the other. He had an old goods wagon mounted on railway sleepers in one of his fields in which he kept the animal foodstuffs. Every morning he cycled down to tend his beasts returning about eight o’clock for breakfast.

He obtained his recreation down at the bowling green where he was recognised as a master. He was indeed selected to play for Scotland many times in the international matches and there was nearly always a silver cup or rose bowl on display in the sitting room. Apart from local tournaments he was Bowls Glasgow and Scottish Champion as well.

Back at Hamilton, and on the opposite side to the Smiths, our neighbour was called Bartle. There was one daughter called Cissy who was about Alec’s age I think. I had little contact with them, but sensed that Granny viewed Mr Bartle with some suspicion. He had a gas engine, I recall, down in his shed at the foot of the garden and this was used to drive a circular saw. He used to saw up railway sleepers and sell the logs, but couldn’t have made a profit for he stopped doing it after a few months and dismantled the whole thing.

On the other side of them lived a schoolteacher called Lucy Gray. She had an Austin 7 and gave us endless amusement when learning to drive. It was nothing to see her up on the pavement, but she mastered it in the end.

When I was ten years old the country was hit by a General Strike. Nearby where I lived was the Hamilton Bent Road Colliery and most of the men were employed there. Times were hard and many of their children went barefooted and often hungry as well.

The miners grew all kinds of vegetables in allotments across from us and produced some really remarkable crops. There was no shortage of manure; Ballantyne’s byre was just down the road, and all the plots were given liberal doses of it. Leeks and marrows were a sort of speciality and the former would be fed on a horrible concoction of sooty water and blood. The marrows I recall were fed by the ingenious method of having a jam jar raised up on top of a brick and this was filled with water containing sugar. A piece of wool was then taken from the liquid and the other end stuffed into a hole pierced just where the stalk joined the marrow. It was truly amazing how that jar would be emptied of liquid overnight.

The miners built a shed from railway sleepers in the allotment, and here they would meet daily and pass the time talking, playing cards and dominoes and even on occasion kite flying in the adjacent field. This pastime was also much in favour with us youngsters and as the field was on a slope it was ideal for this purpose. The farmer was a man called Abe Brownlee and he didn’t seem to mind how many people used his fields.

We made some really fine big kites and by joining balls of string together could fly them way out and up over the town some two miles away and it was not unusual for one or two to be up all day.

During the winter months when the snow lay deep on this field we would get our sledges out and hold races. We never seemed to notice the cold! It was all great fun and cost practically nothing. Money was at a premium, of course, and if we got a penny a week pocket money it was marvellous.

Glebe Street ended where Abe Brownlee’s field began, but changes were in the wind and we awoke one day to find dozens of workmen attacking our favourite stretch of grass with picks and shovels. A slum clearance scheme was to be carried out and Glebe Street was to be extended right up to the top of the field with off shoots branching off at intervals. It was a great blow to the residents but in time came to be accepted and I doubt very much if there are more than a couple of families left who remember it as it was.

To cater for the needs of the new arrivals a small wooden shop was erected across from us and in due course it proudly displayed the name “Allan Law”. He sold newspapers, cigarettes, bread, sweets and many other small items, and the greatest attraction of all was a bell fruit machine, or one-armed bandit. Tokens were used in place of money and any winnings could be used to buy goods.

Allan Law was a much travelled man and I spent a great deal of time in his shop just listening to his tales about all the wonderful places he had been to. He had spent some time as an engineer in Turkey and later on in Russia and had a great admiration for the Russian people. His wife Jean used to come over and help in the shop from time to time, but mostly he was on his own and cooked his own lunch on a little hot plate in the back of the shop.

They had two daughters and one son, and all of them emigrated to Vancouver, Canada, just after the Second World War.

Meantime, however, for me Sunday school was a must and I went to one in the old parish church hall. The way in was via a fairly narrow street behind Excelsior Stores and close by was a small sweet shop where a percentage of the collection ended up each week. Or perhaps on the way home, the machines on the Central Station platform would benefit to the same extent.

The first farm I was allowed to visit was called Hallburn. It was situated between Hamilton and Strathaven and my first sight of it was the windmill down in the corner of the field nearest the main road. Uncle Andrew Kirkland farmed it. He was married to Mary, one of my father’s sisters.

There was one son, John, a year or two younger than me and there was a baby called Mary, but apart from an occasional curious glance I took little notice of her. Her sole interest seemed to be centred on her bottle!

Near to the house was a duck pond, which came in handy for sailing boats, whilst away up at the corner was a wood which was absolutely riddled with rabbit holes. John and I spent a fair amount of time trying to catch one, but were never successful. They seemed to pop up and laugh at us and then, as we approached, dive to safety only to re-appear at another hole.

It was here I had my first experience of haymaking and I vividly remember the glasses of barley water, which were provided to quench our thirsts.

Back at school after the holidays I moved up from the junior section and came under the headmaster John Frew. He lived near the new parish church in a large house set back but overlooking the road. As a frequent visitor to the Public Library I had to pass his house en route and always felt he was watching me – stupid of course, for I’m sure he had better things to do but I must have had a guilty conscience. He caught six of us smoking one lunch time when we had the misfortune to run into him on our way home. One chap called Jimmy Ginn hadn’t noticed him approach and was calling for a light to be passed. That was our undoing and we all got a taste of his strap when got back in school.

The favourite day at St. Johns was sports day when parents and friends could come along and enjoy the spectacle of their sons’ and daughters’ prowess. One could roam about freely amongst the crowd and ice creams were available at 1d or 2d each. There were always a number of side shows, such as coconut shies and so on.

Alec had a bicycle, a “Curlew”, more or less hand made if my memory serves me rightly, and I was now allowed to ride. I had learned to do so on my aunt’s bike at Carluke! It gave me, I’m sure, more pleasure than any other possession we had and enabled me to go further afield and visit Jim Cummings, a school friend who lived up in Cameron Crescent. Jim had a racing model with droop handlebars and fixed wheel, and on the lamp bracket he had a pair of water bottles for long journeys, not that he ever did any to the best of my knowledge.

He left school at fourteen, whilst I went on to Hamilton Academy. I think he did a course in shorthand and typing at Skerry’s College. I don’t remember him ever getting a job. Anyway we remained friends right up to the war when he was killed in action.

Another farm belonging to Uncle Robert was called the Hill of Kilncadzow, just a little way out of Carluke on the Carnwath Road. I only ever went the once and all I can remember was of Mary from Carluke and my other cousins enjoying themselves on a swing in the barn. By the time I next visited Uncle Robert and Aunt Jeannie they had given up the farm and moved into a house in Lanark called “Rosebank”. Later on they moved once again back into a farm called “The Hardens” on the Longformacus Road near Duns in Berwickshire. I went there about twice altogether and my most vivid memories are of the tennis court in front of the house and of the electricity supply. Uncle Robert had his own provided by a room full of large accumulators, which he had to charge up from a motor driven generator each week. Alec was with me on that visit and I remember the commotion that occurred when the bed we shared collapsed during the night.

Uncle Andrew and Aunt Mary had now moved to a larger farm called Greenlawmains at Milton Bridge near Penicuik in Midlothian. There was a large herd of cows here and my aunt used to start milking at 3 o’clock every morning. I spent quite a number of holidays with them and I liked nothing better than to be allowed to get up at 5am and go with my uncle into Edinburgh delivering the milk round the different dairies. We would have a plateful of porridge with double cream before we set off and by the time we got back about 8 o’clock there would be a nice ham and egg breakfast waiting for us.

Our first port of call was at the Glencorse barracks, which was just down the road, and then we drove on along through the sunlit hills till we reached Redpath’s dairy in Morningside. On the way we used to pass lots of small bungalows down to our left and Uncle Andrew would wonder how, “folk could live in a rabbit warren like that.” Then on to Gilmore Place to call on old Mr Weir. He would always have his old black dog with him. He was a kindly soul bewhiskered and full of good advice to, “beware of the wine and the women my boy, especially the women.”

Then on to another dairy near the toll cross. I can’t remember the name, but uncle used to call the owner “lazy bones” and we invariably had to wait for her to drag herself from her bed and open up. We would spend the time having a free read in the newsagents next door or chatting to Jim Noble, one of Uncle Andrew’s friends from a neighbouring farm. The main topic of conversation was to do with the Milk Marketing Board which had just been set up by Walter Elliott, who for his sins had to suffer the indignity of having his effigy burned in Edinburgh.

Once a week, after we had delivered the milk we would call in at McEwans brewery and load up with a steaming hot mixture of hops and grain, which was left over after the beer had been brewed. This was mixed with meal and molasses and fed to the cattle. Haymaking was generally in full swing when I was at Greenlawmains and although I was inexperienced I did lend a hand now and then. Once I was given the job of driving the horse-rake and as nobody volunteered to take over I was stuck with it for the rest of the day. Believe me, a day of bouncing up and down on a bare iron seat is not the best sort of treatment for one’s bottom, but I remember how Uncle Andrew laughed. Right up until the day he died he would remind me of it every time we met.

After a couple of weeks or so at Greenlawmains I would go on to another farm called Milkieston, across the road from the village of Eddleston some four miles along the Edinburgh Road from Peebles. This farm belonged to Johnny Barr who was married to Helen, one of my father’s sisters. There were three children, Willie, Mary and Alex. Mary and Willie were a few years my senior, but Alex was my own age exactly.

Naturally I became quite pally with Alex and we used to get up to all kinds of mischief. Willie being older was already working for his father and as the work was very hard in those days he was of course tired out and ready for bed at a reasonably early hour. He slept in an attic some distance from the bedroom, which I shared with Alex, and I remember one night when Alex and I climbed out of our window and scrambled along the roof till we reached the attic window. Willie was snoring his head off and it was no trouble to open his window and climb in without wakening him. He was lying on his back with his mouth wide open – the temptation was too great and Alex slipped a spoonful of caster-oil into the open mouth. Poor old Willie, he woke up spluttering and gasping and when he realised what had happened he nearly went berserk. We ran down the stairs and back to our own room as though the very devil himself was on our tails. Needless to say we were severely reprimanded next morning.

Once when Mary from Carluke was staying there she shared a bed with Mary Barr. Alex and I crawled under the bed just before they came upstairs and when they got in we bumped it up and down from underneath causing girlish screams. On another occasion we covered ourselves with white sheets and hid in the woods till they came back along the path on their way back from a dance and jumped out on them.

Stan Holloway was singing “With ‘er ‘ead tucked underneath ‘er arm”, Gracie Fields’ “Isle of Capri” was all the rage as was “Blue Moon”, whilst seven year old child star Shirley Temple was giving us “The Good Ship Lollipop.” Greta Garbo wanted “to be alone” and Leighton and Johnston were at their peak. Films of the day were “Sanders of the River” and “Thirty Nine Steps.”